The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies.”1 Environmental justice emerged as a concept in the early 1980s as studies revealed that certain disadvantaged groups of the population, such as poor and minority groups, bear a disproportionate burden of environmental hazards.2 In 2022, the EPA opened its Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights with the goal of providing communities with resources and other technical assistance on civil rights and environmental justice, engaging with environmental justice concerns and providing support for community-led action.3 But what does this have to do with stormwater management?

Hurricane Katrina stands as a stark example of the interaction between stormwater management and environmental justice. Racial disparities in areas affected by the storm made clear that historical infrastructure decisions and economic factors where land at lower elevations was occupied primarily by African-Americans were a significant reason that 70% of those most affected were Black.4 In the storms’ aftermath, a new pre-flood approach to stormwater management and its effect on vulnerable social groups is emerging.5 Until recently, the most common factors in stormwater infrastructure decisions included location, capacity, treatment, suitability, cost and other conventional engineering considerations. The changing physical and social climates on planet Earth now require that additional factors be considered in order to develop for an equitable and resilient future. With increasing calls for decision-making to include diversity, equity and inclusion, social and environmental justice are now important criteria in stormwater project selection. Similarly, improving resiliency to climate change and/or sea level rise is also paramount, as these issues disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities with aging infrastructure.

Environmental Justice and Stormwater

Stormwater infrastructure decision-making is rife with opportunities to incorporate environmental justice concerns. At the watershed planning level, multiple tools are available for identifying environmental justice populations to understand how stormwater projects, from infrastructure installation to stream restoration, will impact surrounding and downstream communities. Databases and maps are now available to identify vulnerable communities including Census Data, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Data and the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool. These tools can be added to the typical engineering design tools to implement stormwater projects that consider more than water quantity and quality but look at their impact with a more holistic community approach. In fact, some communities are doing just that already. This applies to new developments as well as treating existing impervious areas. Identifying environmental justice communities can be a critical piece of stormwater management in the future. In fact, some communities are already using environmental justice in their decision-making process.

Durham County

Durham County, North Carolina has adopted four guiding principles for its stormwater program including: compliance, efficiency, resiliency and environmental justice. As the county develops its plans to meet the requirements of two separate state-mandated nutrient management strategies, these guiding principles will be central to its project selection rubric. The county is taking a two-pronged approach to addressing equity and environmental justice as it relates to stormwater by identifying overburdened and underserved populations within its jurisdiction and where possible prioritizing them for stormwater management activities. For the purposes of this, and consistent with the definitions used by the EPA, an “underserved community” includes those communities with environmental justice concerns or that have vulnerable populations. An “overburdened community” includes those communities with minority, low-income, tribal or indigenous populations, or geographic locations in the state that potentially experience disproportionate environmental harms and risks.6

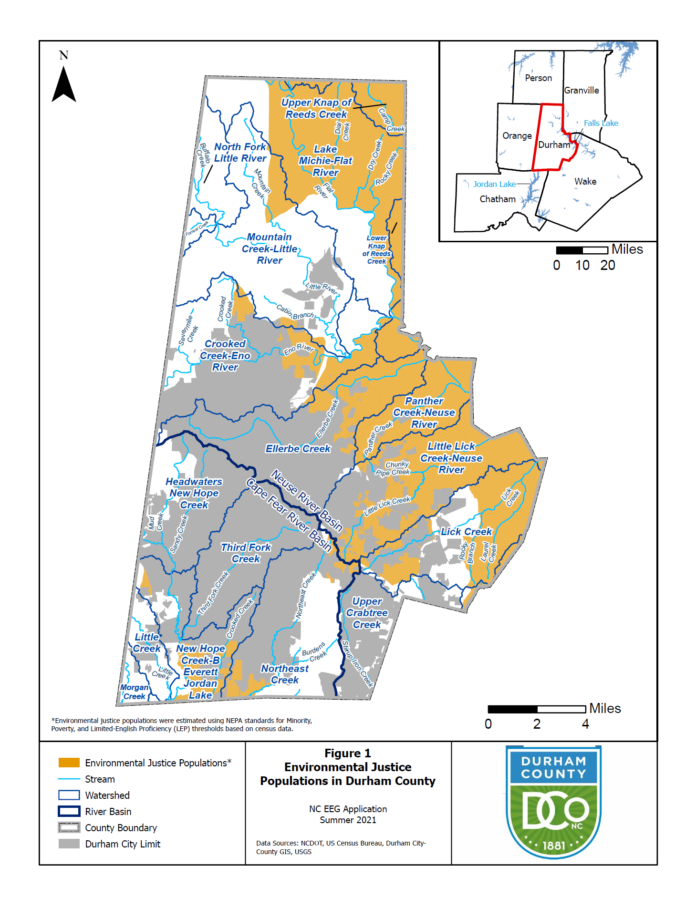

The county understands that many times the first affected — by flooding, water quality pollution and other drainage issues — are often the last to receive information and so it is taking steps to target educational outreach to overburdened and underserved members of its community. Using NEPA standards for minority, poverty and limited-English proficiency thresholds based on census data, the county identified “Environmental Justice Populations” (Figure 1) as the underserved and overburdened populations on which to focus its educational efforts. Recognizing that not everyone has access to the internet or a smartphone, educational efforts will include physical products and in-person events and include Spanish translations to maximize their reach in low-income, minority and non-English speaking areas of the county.

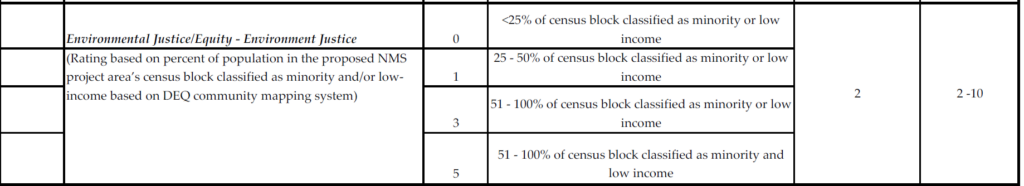

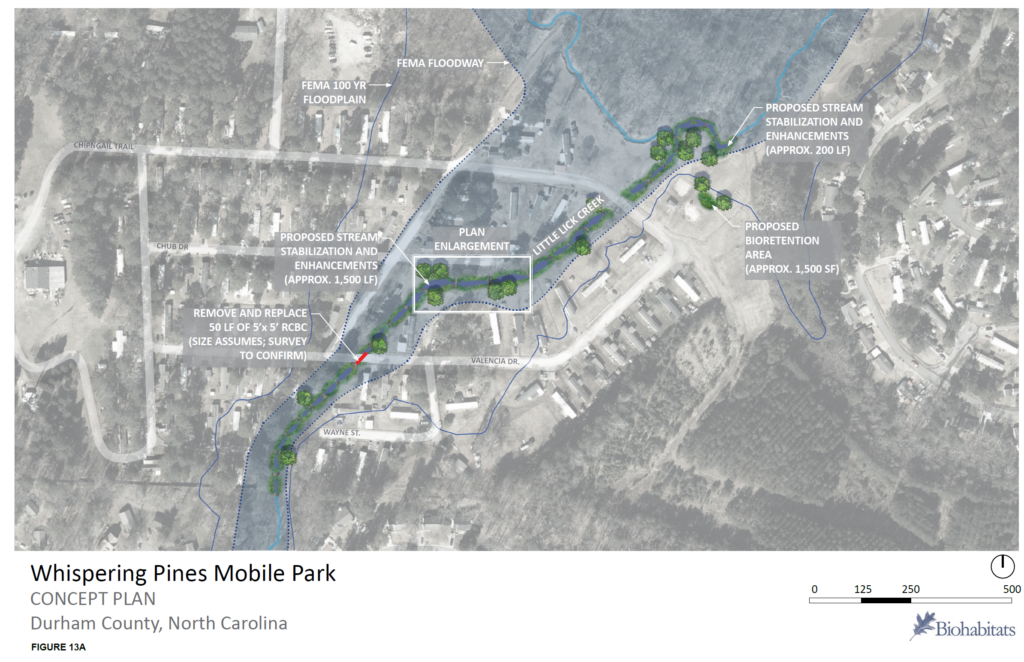

Furthering their commitment to environmental justice, Durham County also seeks to locate stormwater projects in areas with high populations of overburdened and underserved individuals. As the county developed a methodology for selecting stormwater projects to comply with two separate state-mandated nutrient management strategies, it included environmental justice/equity as a criterion in its project scoring rubric (Figure 2). Projects receive credit for environmental justice/equity based on census block data classifications for minority and/or low-income populations. The county’s first two stormwater projects, a bioretention pond at a middle school with an over 80% minority student body and a stream restoration running through a mobile home park, both scored maximum points in this category. These projects are scheduled to begin in 2024 and 2026 respectively (Figures 3 and 4).

Conclusion

Incorporating environmental justice principles into stormwater decisions plays an important role in assisting underserved and overburdened communities who have long dealt with flooding, drainage and water pollution concerns, oftentimes literally in their backyard. The tools are available to add environmental justice and equity to the traditional engineering tools for new stormwater infrastructure design and placement, whether for new development or treating runoff from existing impervious surfaces. Durham County is only one example of how local governments can include environmental justice in their policies and project identification process.

References:

- EPA Environmental Justice Website: www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice.

- Holifield R. 2012. “Environmental justice as recognition and participation in risk assessment: negotiating and translating health risk at a superfund site in Indian country.” Annual Association of American Geographers. 102:591–613.

- EPA Environmental Justice Website: www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice.

- Morse R. 2008. “Environmental Justice Through the Eye of Hurricane Katrina.” Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies Professional Paper. p. 3–4.

- Meenar M., Fromuth R. & Soro M. 2018. “Planning for watershed-wide flood-mitigation and stormwater management using an environmental justice framework.” Environmental Practice, 20:2-3, 55-67.

- EPA Environmental Justice Glossary: https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice/ej-2020-glossary.

About the Expert

Ryan D. Eaves, PE, CFM, CPESC, is the Stormwater and Erosion Control Division Manager for Durham County in Durham, North Carolina. A native of Athens, Georgia, Ryan holds a bachelor’s in environmental science from Virginia Tech and a Master of Public Administration from the University of Georgia. He has over 17 years of local government stormwater and erosion control experience.