Vegetation establishment is recognized as the most effective Best Management Practice for stabilizing disturbed ground to prevent erosion and is often a prerequisite for receiving a Notice of Termination for a permitted construction project. Many projects have specific requirements for the type of vegetation that must be replanted and most have a threshold for percent establishment, typically 70% of the pre-disturbance stand. Not all revegetation species are grasses, some are legumes and forbs. Sometimes the seeds specified for revegetation are native ecotypes and other times they are turf and/or forage species. Have you ever wondered where the seed comes from?

The Pacific Northwest of the United States has long been a place of myth, legend and lore; from the indigenous people who lived in the region for millennia prior to the arrival of European settlers, to the exploits of Louis and Clark in their quest for manifest destiny, to the elusive Sasquatch or Bigfoot. But did you know that a majority of the world’s seed production of cool season turfgrass and forage species comes from this region as well?

In 2017, Oregon recorded 400,000 acres (162,000 ha) of grass seed production grown on approximately 1,500 farms with most of that acreage located in the Willamette Valley of Oregon. The Willamette Valley alone accounts for two-thirds of the United States’ cool-season grass seed production earning it the title, “Grass Seed Capital of the World.”

Why Willamette Valley?

The Willamette Valley is 150 miles (240 km) long and surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Oregon Coast Range to the west, the Cascade Range to the East and the Calapooya Mountains to the south. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley from its headwaters in the mountains just south of Eugene, Oregon to its confluence with the Columbia River in Portland, Oregon. There are three main reasons the valley leads the nation in grass seed production: climate, soils and agricultural history.

- Climate

The Willamette Valley is located halfway between the North Pole and the equator with four distinct seasons. The temperate climate and wet winters provide a long growing season for the plants to develop while the arid summers support pollination, seed head development and harvest. This makes the Willamette Valley an ideal place to produce high quality seed. While it is not uncommon to experience precipitation from October through June, the region can usually count on 90 to 100 days without precipitation during the summer months. That allows grasses and legumes like clovers and alfalfa grown in Oregon to be cut, windrowed and allowed to dry in the field prior to harvesting with a combine harvester (Figure 1). Other seed producing regions of the world have to put the seed through a commercial process that heats the seed to dry it out. This process has the potential to damage the seed and subsequently affect germination rates. The heating process is also considerably more labor and resource intensive than allowing seed to dry in the field. - Soils

The Willamette Valley has an extraordinary variety of soil types with over 2,000 distinct soil classifications. This abundant diversity is owed to one specific force of nature: erosion. The Missoula Floods inundated the valley multiple times between 13,000 to 15,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. Periodic rupturing of Glacial Lake Missoula’s ice dams caused flood waters to sweep down the Columbia River stripping rich glacial and volcanic soil from eastern Washington. The water from these floods filled the entire Willamette Valley to a depth of 300 to 400 feet (91 to 122 m) above current sea level and deposited soil one-half mile (1 km) deep in some areas as the waters subsided.1,2 - Agricultural History

In the 1820s the Willamette Valley was widely promoted as a “promised land of flowing milk and honey” due to its numerous waterways, highly fertile soils and broad, flat plains. It was the destination of choice for many immigrants who undertook the perilous journey along the Oregon Trail by oxen-drawn wagon trains. The Willamette Valley was home to a variety of native grasses prior to white settlement. Non-native grasses had replaced many wild grasses by the late 1800s due to the introduction of livestock and overgrazing (Figure 2).

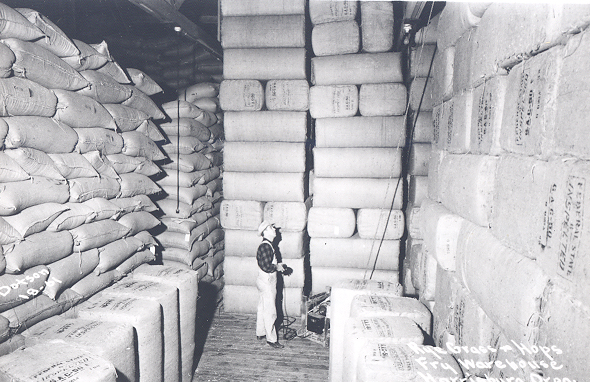

In 1921, Forest Jenks of Linn County planted the first commercial ryegrass in the valley. The ryegrass was especially well adapted to the wet soils and soon became an important crop. Grass seed quickly became an excellent alternative crop for the highly erodible soils found in the valley’s foothills, and by the 1940s seed production rapidly increased due to agricultural mechanization and the introduction of new grass varieties. Oregon growers today produce essentially all of the United States’ commercial production of annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), bentgrass (Agrostis spp.) and fine fescues (Festuca spp). They also produce significant amounts of Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pretensis), orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata), and tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea).3 In 2017, Oregon growers produced over 600 million pounds of cool-season grass seed crops consisting of over 950 varieties across eight grass species. The Willamette Valley has nearly 400 seed conditioning plants to clean and package the seed for market once the harvest is complete.

Oregon growers are widely recognized for their expertise in seed production and most national and international seed companies have operations located in the Willamette Valley. Many of these seed companies have breeding programs with research and development facilities (Figures 3 and 4). Did you know that it can take up to 20 years to develop and release a new cultivar that produces true-to-type progeny from seed? Cultivars that prove to have traits that are measurably distinct, uniform and stable may be granted a plant variety patent and become a named variety.

Breeding programs often conduct grower yield trials to screen potential new cultivars prior to publicly releasing them to ensure they produce acceptable seed yields. It doesn’t matter how good the variety a seed company develops is if the resulting plants don’t yield a commercially viable seed crop. Multiple breeding efforts today are focused on developing more sustainable turfgrass and forage varieties that perform well with less water and fertilizer while tolerating higher thresholds of heat, drought and salinity.

The temperate climate of the Pacific Northwest combined with the fertile soils of the Willamette Valley make it an ideal place to produce turfgrass and forage seeds. So the next time you walk through a park, watch your favorite sporting event played on grass or inspect vegetation on a construction site, there is a good chance that seed started its journey in the Willamette Valley of Oregon.

References

- Allen JE, Burns M, Sargent, SC. Cataclysms on the Columbia: A layman’s guide to the features produced by the catastrophic Bretz floods in the Pacific Northwest. 1986. Pages 175–189.

- Orr EL, Orr WN, Baldwin EM. Geology of Oregon. 1964. Pages 211–214.

- Giombolina K. Grass Seed Industry. Oregon Encyclopedia, A project of the Oregon Historical Society, www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/grass_seed_industry.

About the Expert

Brian M. Free CPESC, CPSWQ, CPAg employs a holistic approach to solving many of today’s challenges in erosion control and stormwater management and has successfully helped clients across multiple market segments.